Are stereotypes grounded in fact?

- Mark J. Panaggio

- Jun 8, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Jun 11, 2020

In the last post, I discussed the “mere-exposure” effect and how neutral and positive exposure has been shown to decrease prejudice and lead to more positive perceptions of others. In this post, I want to take a look at how negative interactions can color our perceptions for the worse and explore whether our prejudices about people from different communities are necessarily grounded in reality.

Have you ever heard someone admit to harboring a negative view of a particular racial or ethnic group and justify it by referencing a bad experience they had? Whether it was a neighbor who was rude to them or a coworker who was lazy, I have heard these sorts of anecdotes from people I know on numerous occasions. The human mind seems to be hard-wired to find patterns, so it is natural for us to make generalizations based on a small number of experiences. When I hear stories like that and before I judge, I try to put myself in the speaker’s shoes. Suppose I had a coworker who showed up to work late and who had a lousy attitude and who didn’t pull their weight. How would I respond? It doesn’t make it right, but if that was one of my only interactions with people of that race, then I have to admit that I too might be tempted to generalize and allow those negative interactions to color my perspective of other people as well.

There are a number of well-documented behavioral phenomena that can explain this tendency. First off, people have a negativity bias. We respond more strongly to negative events than to positive events and they tend to come to mind more easily. As a result, one bad experience might offset multiple positive experiences. When estimating the probability of an event, we tend to use a mental shortcut known as the availability heuristic in which events that are easier to recall have a disproportionately large effect on our estimates. This means that we tend to overestimate the likelihood of rare events if they are memorable. Additionally, we are susceptible to the illusion of validity which suggests that our minds are so good at finding patterns that we can often “discover” patterns that aren’t even there and, as a result, overestimate our ability to make predictions.

I was thinking about these biases and our tendency to form generalizations based on limited data recently when a question came to mind. I don’t want to be prejudiced, but I also can’t discount every negative experience that people have. Is it reasonable (from a statistical perspective) to conclude that there is a grain of truth to these generalizations? In other words, do these prejudicial generalizations need to be true for them to be take root in society?

To make this more concrete, let’s return to the example from earlier, suppose that a number of people of race A have developed the negative perception that people of race B tend to be lazy due to their own negative experiences (which for the sake of argument, I will assume are legitimate). Is it necessarily true that people of race B actually are more likely to be lazy? Or can such biases emerge even if they have no factual basis?

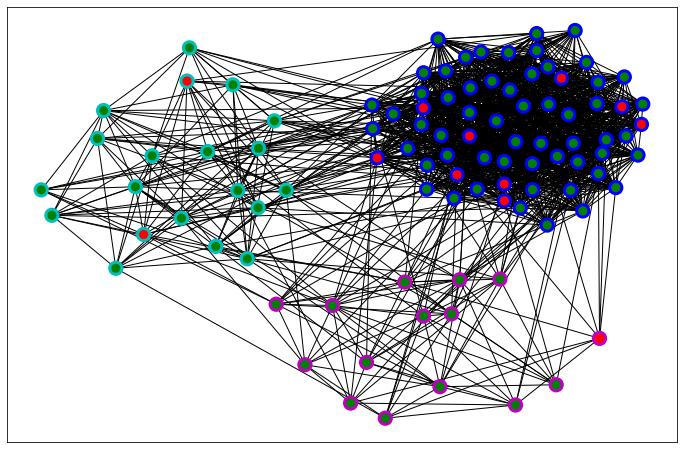

To test, this I decided to use take the standard statistical approach of assuming a “null hypothesis” (i.e. that biases did emerge with no basis in reality) and then looking for the evidence to the contrary (i.e. looking to see if this is actually implausible). I started by generating a random social network that is assortative just like real world social networks. An example of one such network is shown below:

Here the dots represent people and the black lines represent connections (friendships and/or interactions) between them. In this particular network, there are three distinct communities (indicated by the colored borders) which you can think of as representing different racial or ethnic groups. The blue community is the majority and the smaller cyan and magenta communities represent minorities. This network is structured in such a way that individuals are far more likely to connect (probability 0.5) to members of the same community than they are to members of different communities (probability 0.1 or 0.2). In other words, this network is assortative by community.

To simulate the possibility of negative interactions that might promote prejudice, individual vertices were randomly assigned a label of naughty (red) or nice (green) in such a way that the proportion of naughty people is the same (10%) for all 3 groups to capture the idea that some interactions between groups will be negative (more on this later). In this particular network, I kept the system small for visualization purposes so the proportions don’t work out to be exactly the same, but in the (larger) networks I discuss later on, these proportions defined to be identical. In other words, members of different communities are equally likely to be naughty.

If a given vertex is connected to a naughty vertex, then I assumed that they perceive the interaction as negative and if they are connected to a nice vertex, then I assumed that they perceive the interaction as positive. To illustrate how prejudices arise, let’s suppose that if enough (for illustration purposes I will use 20%) of your interactions with members of a particular community are negative, then you will develop a negative (prejudicial) perception of the entire community. You can think of that as a simple way of capturing that idea that when negative interactions are rare you might be willing to chalk them up to a few bad apples, but when they are sufficiently common you might start to make generalizations about the group as a whole. Notice that since only 10% of people from each community are naughty only people who have noticeably more negative interactions than average will develop prejudices in this model.

We can then ask the question: how will the members of each community view each other? I investigated this by computing the proportion of vertices in each group that had negative perceptions of other communities through the following process:

1. Generate a random network, each with a breakdown of 64% blue, 20% cyan and 16% magenta which is close to the breakdown of white, Hispanic and black individuals in the US.

2. Randomly label naughty and nice nodes, keeping the proportion of naughty nodes exactly the same for all three groups.

3. Look at the neighbors of each vertex (representing a person) individually to determine whether this individual will develop a negative perspective of members in its own community as well as the other communities.

4. Count up the number of prejudiced individuals from and toward each community.

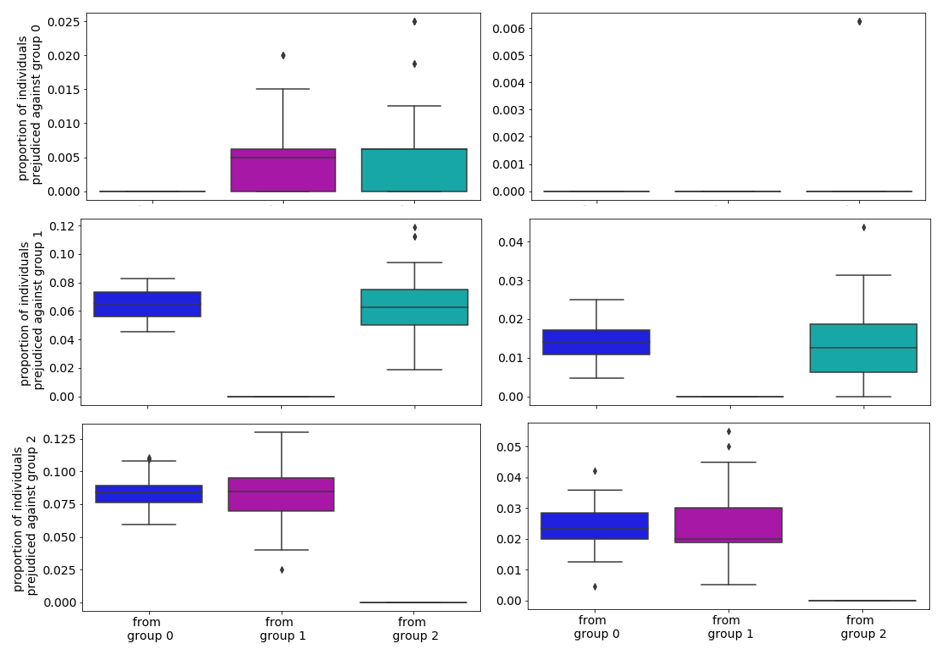

I repeated this process a total of 1000 times. The results are displayed below using a collection of boxplots. The vertical axis indicates the proportion of individuals that are predicted against a given group with group 0 representing the majority (blue, 64%) community, group 1 representing one minority (magenta, 20%) community and group 2 representing the other minority (cyan, 16%) community. The three boxes represent the attitudes of members from each of the three groups. Note that if you are unfamiliar with a boxplot, you should focus on the middle line through each box which represents the median (typical) outcome.

One the left, I am showing the scenario where the probability of connection between communities was 0.1 and on the right it is 0.2, meaning people in the networks on the right have more exposure to members of different communities than the ones on the left. There are a few interesting things to note:

1. The first thing to observe is that there is no empirical basis for prejudice in the experiment, and yet a nontrivial segment of the network becomes prejudiced anyway. There are exactly the same proportion of naughty people in each community, so, any prejudices that emerge are the result of random chance and not due to differences in the “niceness” of the three communities. This suggests that there is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The existence of prejudice without the “kernel of truth” is quite plausible.

2. Secondly, the median values of prejudice are noticeably higher on the left than on the right (most of the corresponding boxes don’t overlap at all). This means that less connections between different communities promote prejudices and conversely, higher connectivity between communities decreases prejudice. This can be understood as a consequence of the law of large numbers which suggests that the proportion of negative interactions will be closer to the average (10%) in larger samples, i.e. when there are more connections between communities. In other words, when you have a small number of interactions with a group, one bad in interaction can have an outsized effect on your perceptions, but as you increase the number of interactions, the good will tend to offset the bad and your perceptions of that group will tend to become a more accurate estimate of what the group is actually like. This seems to be consistent with my experience. Anecdotally, I have found that most of the people who admit to having a negative perception of people of a particular race or ethnicity (which may be a small subset of those who actually have negative perceptions) are often the same people who have few meaningful interactions with that group and who have been influenced by a small number of bad experiences.

3. The third thing to note is that the majority group tends to exhibit the strongest prejudices. No group is prejudiced against their own community, but a nontrivial percentage (5-10%) of members of the majority (blue) community are prejudiced against members of the minority (magenta and cyan) communities. No other group has such strong prejudices against both groups.

Interestingly, if you increase the probability of connection between communities even further to 0.4 (not shown), so that there are almost as many interactions between communities as there are within communities, prejudice disappears completely.

The results of this experiment are surprising. They suggest that people and even large segments of a community can develop negative perceptions about members of another community that are grounded in real experiences even when there is no statistical difference between the communities. I must confess that in the past I assumed that, although widespread prejudices and negative stereotypes are harmful and worth avoiding, they probably contained a kernel of truth. This analysis suggests that need not be the case. Prejudice can emerge due to the relative scarcity of interactions between communities even when there is no factual basis for the negative perception.

When we find ourselves being influenced by prejudice and/or negative stereotypes, it is worth asking the question: Is it possible that I am overreacting to a small number of negative interactions? If so, then one way to remedy that is to seek out positive interactions with the very people who we are tempted to view in a negative light.

PS. You might have noticed that I never actually answered the question. Are stereotypes grounded in fact? I simply showed that negative stereotypes need not be grounded in fact to persist. I don’t know the answer to that original question and it will undoubtedly vary depending on the stereotype. Answering such a question completely would require more time and data than I have available. However, I hope that showing that stereotypes can emerge even when they are false might cause people to reconsider justifying their biases based on their limited experiences. Given that negative stereotypes are detrimental to our ability to treat one another with love and respect (regardless of whether they have kernel of truth), I believe that we should avoid reinforcing them through our attitudes, our words and our actions as much as possible.

Comments