Coronavirus conspiracies and moral matrices

- Mark J. Panaggio

- Aug 1, 2020

- 14 min read

Lately I have seen quite a few posts on social media that can be paraphrased as follows:

[Insert villain] is destroying our society by using [insert technology, policy or activity] to [insert nefarious goal].

The cast and characters change, but the general thrust of the conspiracy theory is the same. Don’t believe me? Try filling in the blanks above. I've offered a few suggestions in the table below. I bet most of the things you come up with will sound eerily familiar.

Most of these theories are so nonsensical that they aren’t worth addressing. They can be easily debunked with even a cursory examination of the facts. So, when I see these sorts of posts, I am tempted to respond by laying out all the evidence in the hope that this will convince people not to be deceived. However, the more I learn, the more I realize how futile that would be. Even when a conspiracy theory is thoroughly debunked, believers often double down or just find a new conspiracy theory to adopt. I have concluded that this occurs because believing in conspiracy theories has nothing to do with reason or facts or evidence.

Have you ever noticed that, when a person embraces a conspiracy theory, the villain is almost never an individual that they previously held in high regard? People don’t believe conspiracy theories about people or institutions that they trust. They don’t adopt conspiracy theories because new and troubling evidence came to light that changed their mind. They believe conspiracy theories when the theory points the finger at people that they already despise. The details of the theory are almost irrelevant. The important thing is that the theory confirms what people already “know”: that this particular villain is evil and corrupt. People believe in conspiracy theories because they are predisposed to think ill of someone or something and they are eager to accept any narrative that justifies this predisposition. In other words, a willingness to believe in conspiracy theories is yet another example of confirmation bias (something I have been harping about a lot lately).

As an example, I was chatting with a (right-leaning) friend the other day and the conversation turned to COVID. I was taken aback when this person then proceeded to explain to me how after the election in November this would all just go away. In other words, he was suggesting that all of the concern over the pandemic was essentially a political game and that once the game ends, the “pandemic” would subside, and life would just return to normal.

My first reaction was to think of all of the evidence that underscores the implausibility of this theory. For one, there is the whole issue of the virus itself. It is hard to portray the situation as a political spat when over 4 million people have been infected and over 150,000 have died. I know some people are skeptical of those numbers, but when you look at the results of antibody tests (which find that the number of people who have been infected could be around 10x as high) and the number of excess deaths (as of two weeks ago, there had been over 160,000 more deaths in 2020 than in a typical year), it becomes apparent that those numbers are more likely to be underestimates than overestimates. Back in April and May, there were some who pointed to the fact that most of the hardest hit states at that point had Democratic governors as evidence this was just “hysteria” that was manufactured by left-leaning politicians. This has proven to be nonsense. The virus has now hit both right-leaning states such as Florida and Texas as well as left-leaning states such as New York and California. At this point, the number of cases in each state is more correlated with population than political affiliation. There could not be such uniformity in a manufactured crisis without complicity from members of both parties. But in a genuine pandemic, that is precisely what you would expect. The reality is that this virus does not care about your politics. The fact that blue states were hit hard early had little to do with governors and a lot to do with geographic and demographic factors.

Furthermore, there is the matter of the implausibility of such a suggestion. The top 5 countries by number of cases are:

United States 4.6 million (North America)

Brazil 2.6 million (South America)

India 1.7 million (Asia)

Russia 0.8 million (Europe/Asia)

South Africa 0.5 million (Africa)

Notice anything interesting about that list? They are all from different continents! The coronavirus has impacted nearly every country on the planet from every corner of the globe. I have heard from friends in Europe, Africa and South America during this time and they have all experienced lockdowns more restrictive than the ones we have experienced in the US. So, if you want to make the argument that the uproar and disruption we have experienced is evidence of a conspiracy by the Democratic party to undermine the president (an accusation I have heard on numerous occasions), then you need to account for the fact that the leaders of just about every country in the world are in on it. Our countries cannot even agree on whether to use the same system of units (metric or imperial), or which side of the road to drive on (left or right), or whether to call it soccer or football. The idea that the leaders of every country in the world could conspire together to manufacture a global crisis is simply implausible.

Clearly there are reasons to be skeptical of theories like this. However, it ultimately dawned on me that none of that matters. Conspiracies are about more than ignorance and shoddy reasoning. I could (and did) explain all of that and of course it made no difference. Deep down, the reason people believe this theory and others like it is that they are deeply distrustful of the Democratic party and they see it as a threat to their values and way of life. The claim that this crisis is largely a hoax simply validates these fears. Is there substantive evidence that this is a hoax or that the data is being artificially inflated? Of course not, but none of that matters. When you want to believe that the Democrats will stop at nothing to destroy all that you hold dear, then a post on Facebook that claims that the colleague of a friend of a friend of a friend heard that doctors were being offered money to falsify records is enough.

As a scientist, the silliness of the conspiracy theories trouble me, but as a human being it is our willingness to believe them that keeps me up at night. I have been wrestling with this idea for quite some time and in this post, I would like to examine some of my conclusions about why we are so willing to believe such horrible things about our political opponents and why a shift in perspective is needed if we are going to be able to coexist and work together.

To start, let’s think for a moment about this theory that the uproar over the coronavirus is merely political maneuvering. If that were true, what would it say about the participants in this conspiracy? It would mean that they are so corrupt that they are willing to destroy our economy, sacrifice the education of our children, and disrupt the lives of millions of people (billions if you count the rest of the world) all for the sake of winning an election. In that scenario, they would be responsible for needlessly preventing those who are sick from receiving medical care and those who are dying from saying goodbye to their loved ones. They would have caused the worst unemployment since the great depression and for what? To improve their odds in an election in which they already had momentum?

This is the thing that I find unfathomable. I have as many quibbles with the Democrats as the next guy (although I have plenty of quibbles with the Republican party as well), and I know that the left and right do not like each other, but has it really gotten that bad? Do we really think so little of each other that we would be willing to believe that those on the other side of the aisle would intentionally do something so horrible? Do we really think that our political opponents are that depraved? For many, the answer seems to be yes. And if that is the case, then what chance is there that we will ever be able to work together to address the challenges facing this country?

A book I was reading recently helped shed some light on why people are willing to believe this. The book is called “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion” by Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist at NYU. Now, I do not agree with everything (or even most things) in this book, but I thought his discussion of how morality frames our politics was particularly insightful and illuminating. Haidt argues that our approach to morality is shaped by six foundations that he studied empirically through a collection of different experiments:

Care/Harm: The importance of caring for one another and avoiding behaviors that cause harm to others.

Liberty/Oppression: The importance of preserving personal freedom and opposing those who dominate and oppress others.

Fairness/Cheating: The importance of making sure people get what they deserve (proportionality) including rewards for those who work hard and create value and punishment for those who try to exploit the productivity of others.

Loyalty/Betrayal: The importance of preserving and even sacrificing for the preservation of one’s family, community and country.

Authority/Subversion: The importance of honoring and respecting authority and tradition.

Sanctity/Degradation: The importance of purity and avoiding self-contamination.

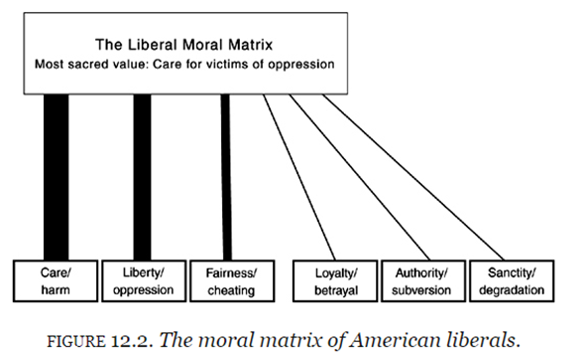

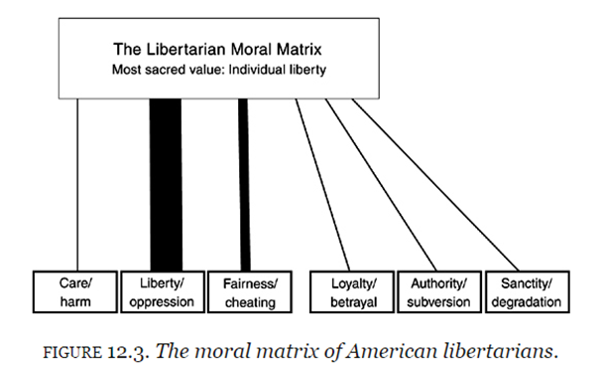

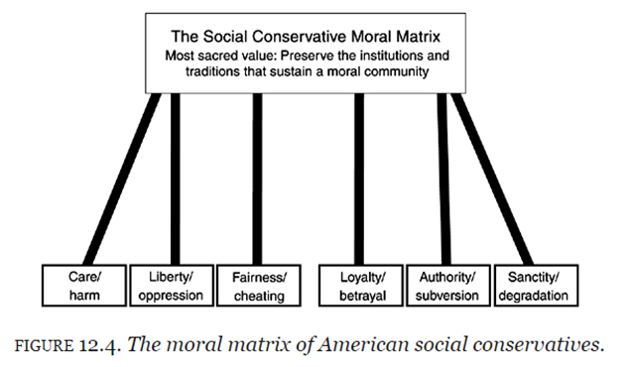

Haidt found that while people of different political persuasions share the same six foundations, they tend to assign radically different weights to those factors. This is illustrated by the diagrams below where the thickness of the line represents the emphasis placed on each moral foundation. He refers to this set of foundations and the emphases that we place on them as our “moral matrices” (see below for some diagrams) and points out how they shape our view of the world and how we often struggle to interpret other people’s actions through any moral matrix other than our own.

For liberals, the first three foundations are paramount, and as such, they tend to emphasize the alleviation of suffering and oppression and focus on fighting for equality. They tend to be less concerned with patriotism, the preservation of institutions or violations of traditional notions of purity (in so far as they do not directly harm others).

Libertarians on the other hand emphasize liberty and fairness above all else. They are very concerned with the personal liberty and rights, and the preservation of wealth and property. They are willing to allow for some suffering if addressing it would require sacrificing freedom or proportionality.

Conservatives in contrast tend to value all six foundations and place significantly more emphasis on loyalty and patriotism, have more reverence for tradition, and value sanctity in ways that the other groups do not. As a result, they may be willing to accept restrictions on personal behavior when those restrictions are focused on preserving sanctity. I should point out that Haidt describes himself as a progressive turned moderate who leans democratic, but who is deeply concerned about the dismissiveness and antagonism coming from all sides and who believes that all three perspectives offer important insights about human nature and what makes for a peaceful and moral society.

These brief descriptions just scratch the surface of his book, and not everyone fits neatly into those three boxes. However, when you combine this framework with the rise of social media (which can amplify our tribal tendencies) and certain shifts in our approach to parenting and education, it paints a picture that can explain much of the polarization and downright hatred we see in politics today.

To understand why, consider what happens when a politician endorses a policy that violates your moral sensibilities. Maybe you think it is unjust or that it would cause harm to some people or that it would cause damage to the institutions that you consider to be sacred. How do you view the person endorsing that policy? Do you condemn them and assume that they are corrupt? Or worse do you conclude that they are seeking the destruction of your way of life because according to your moral matrix what they are doing is wrong? Or, do you first pause to consider why they might think that policy is a good idea and whether they might have a different moral matrix in which that policy is actually the right thing to do?

If you are limited to your own moral matrix, then you have no choice but to view the other side as the embodiment of evil. Stuck within their own matrix, progressives must argue that conservatives and libertarians are immoral because they have little concern for the poor as evidenced by their opposition to wealth redistribution. Libertarians must argue that progressives and conservatives are immoral because they desire to impose their beliefs on other people and are willing to sacrifice liberty to do that. Conservatives must argue that progressives and libertarians are immoral because the are willing to compromise sanctity and tradition on order to achieve other goals.

However, a step outside of your moral matrix offers an alternative interpretation. It allows you to ascribe good intentions to those you disagree with. Viewing the world through the eyes of another is not easy. It requires patient reflection. It requires awareness of the evidence, experiences and assumptions behind your beliefs and recognition that those may not be shared by all. It requires a willingness to listen to the other side and to make a concerted effort to understand it. Most people are not willing to do that. It is much easier to dismiss and condemn than to empathize. However, when you are actually able to understand someone else’s perspective, you often find that they too are doing what they believe to be right, but you have different definitions of right.

Stepping outside your moral matrix does not mean abandoning the notion of moral absolutes and embracing relativism. You don’t have to stop thinking that you are right and that they are wrong (although a willingness to at least consider the possibility can be healthy). You just need to realize that it is not necessary to attribute the other side’s “wrongness” to some deep-seated and willful malevolence. It may be that they are just operating under different assumptions. Sure there are plenty of situations where politicians have selfish and/or perverse incentives, and there are some who are genuinely corrupt, but isn’t it possible that there are people on both sides of the aisle that genuinely want to help the country but simply disagree about the best way to do that?

The problem with conspiracy theorists who embrace narratives like “the coronavirus hysteria is an elaborate hoax perpetrated by the Democrats who are intentionally destroying the economy for political gain” is that they are often unable to step outside their moral matrix. They concluded that the Democrats were evil long ago because they do not approve of the Democratic agenda. It offends their moral sensibilities, and they cannot or do not consider the possibility that the Democrats might just be doing what they believe is right. As a result, these conspiracy theorists are all too eager to attribute malicious intent to anything that their political adversaries do. Once you have embraced that mindset, it is not such a large leap to conclude that they would willingly “destroy our economy” to help their election prospects.

The same goes for other conspiracies. If you are already distrustful of scientists and doctors because they advocate for things that do not fit within your moral matrix, e.g. government regulations to combat climate change or a pandemic at the expense of free markets and skepticism about the supernatural, then it doesn’t take much to convince you that they are part of some hidden and sinister scheme. Believers of conspiracy theories are often unable to step outside their moral matrices and this prevents them from seeing a more benign explanation: that these actions may be completely consistent with a different moral framework.

This makes a huge difference for our political discourse. Viewed through your own moral matrix, political adversaries can only be seen as evil and as a threat to be opposed at every turn. There is no point in compromise or cooperation when you believe that they are intent on causing harm and destruction. However, if you step outside your moral matrix, you can instead see your opponents as well-intentioned even when you disagree with their methods or even their objectives.

The point is that even if you believe that you are right and they are wrong, there can be common ground. If both sides want the same thing, what is best for the country, and if both recognize that disagreements are shaped by different (but not completely disjoint) moral foundations, then that creates an opportunity for discussion about our differences and recognition of our commonalities. It gives us a starting point from which to have productive debate and even to attempt to persuade each other about which view of “the good” is correct. But if we fail to do that, we will inevitably assume the worst about the other side, and some may even fall for the ever so appealing conspiracy theories that validate our worst fears.

Returning to the issue of the coronavirus, I recognize that we are not all going to agree on how to handle this crisis because we start from different moral matrices. And it IS a crisis as this blog has repeatedly established. If you are a progressive, your concern for minimizing harm may supersede concerns over the loss of freedom and the fairness of restricting people’s ability to work. If you are a libertarian, your concern for preserving freedom may supersede concerns over the human toll caused by an uncontained outbreak. And if you are a conservative, your concern for the continuation of the sacred traditions that you hold dear such as church gatherings, weddings and graduations may supersede concerns over the risk of spreading the virus. However, before we condemn one another, I think it is worth asking the question: is there a common ground? Can we fight the virus together in a way that protects each other, preserves freedom and guards our cherished institutions? I tend to believe that there is.

I believe that it is possible for us to protect one another by taking responsibility for our own actions and for how those actions affect each other independent of government mandates and restrictions. If we were willing to listen to recommendations (most of which have a sound scientific basis) would mandates even be necessary? I believe that if we were willing to embrace true freedom including the freedom to choose not to exercise your rights for the sake of your fellow man, then the modest inconvenience of wearing masks would not be such a hot button issue. Should you be forced to wear a mask? Perhaps not, but should you wear one anyway? If you care about your neighbors, then absolutely. I also believe that we are capable of being far more resourceful than we realize. We can find creative ways to continue to celebrate and mourn and worship together without putting our friends, neighbors and families at risk. But we will never be able to do that if we keep believing the worst about each other.

The sad truth is that there is one way to complete the mad lib from the beginning of the post that makes sense and that is overwhelmingly supported by the evidence:

[The coronavirus] is destroying our society by using [our own cells] to [replicate and spread its genetic code causing widespread sickness and death along with both economic and emotional devastation].

This is the threat we should be concerned about and it is not a hoax. It is not a political game. It is real. Real people are getting sick and real people are dying, 150k and counting, with little sign of slowing down. I learn about more people in my social circles who have lost loved ones every day. As a result, people are afraid and many are both voluntarily and involuntarily avoiding some of the activities that have long sustained our economy and social fabric. Because of this, people are hurting, struggling financially and battling a sense of isolation beyond they have ever experienced before.

So, please, can we stop pretending this is about politics and can we start giving each other the benefit of the doubt? Maybe, if we were willing to look beyond our own moral matrix and see the world through a different lens, we might be slower to accuse our political opponents of such awful things. We might be less willing to believe in far-fetched conspiracies, more willing to carefully consider the evidence and better able to understand what is really going on. We don’t have to agree on the best course of action, but we should at least be able to agree on the facts. We will only be able to do that if we stop looking for convoluted reasons to be suspicious of each other and instead focus on working together to address the challenges that are ahead.

PS. If it seems like I am being particular hard on the right, it is because I am. I could just as easily point to many of the same behaviors on the left (albeit pertaining to different issues). However, I single out the right because it is the side that I am closest to. It includes so many of my friends and relatives, coworkers and church family. I know how they think because I am one of them, and WE need to do better. If this crisis has proven anything, it has shown that we need to look in the mirror, reevaluate our priorities and reflect on whether we are actually living out the things we claim to believe. Far too often we seem to put politics ahead of truth and we, of all people, should know better.

A reader pointed out that my focus on conspiracy theories that have been embraced by some on the right and my disclaimer about being harder on the right might cause some to conclude that I think this is a uniquely right wing problem. I don't, and it isn't. One study by Haidt et al. (the author of the book I referenced) asked people to answer questions about morality as they thought the other side would answer and they found that both liberals and conservatives overestimated the moral differences between typical conservatives and typical liberals but that conservatives actually did a significantly better job of representing the perspective of liberals than vice versa. This suggests that an inability to empathize …