Echo chambers and political polarization

- Mark J. Panaggio

- Jul 29, 2020

- 10 min read

This is part 2 of a series on social media and its effects on society. You can find part 1 here. Also, if you enjoy these posts. Please consider subscribing via the link above. That way you will get an email update every time a new one is posted and you will have the option of commenting on the posts.

In a previous post, I discussed how social media platforms make it easy for information to spread in much the same way that viruses do, allowing content to “go viral” and spread throughout our social networks, often to our detriment. Today I would like a look at two additional effects of these new venues for public discourse: the formation of echo chambers and the enhancement of political polarization.

During the early days, social media platforms were built around each individual’s personal page. If you wanted to share content, you would post it to your page and the friends who visited your page could see it and respond to it. In some respects, this was not all that different from the way that people interacted for decades before: just like sending an sending a letter, or making a phone call or even sending an email, one party had to make a conscious choice to seek the other person out in order for interactions to take place.

That all changed with the introduction of the news feed. Suddenly when you logged on to Facebook or Twitter, updates from all your friends were aggregated in one centralized location and you could scroll to browse them as long as you wanted. Initially these feeds were presented chronologically allowing users to see what they had “missed” when they weren’t logged in. However, to some this felt like drinking through a fire hose. It was simply not possible for most people to sort through all of the pictures and status updates to get to the information that was actually of interest, so some people didn’t bother. As a result, the feed did not hold people’s attention quite as long as its creators might have hoped.

Then engineers stumbled upon a brilliant idea: What if the information was sorted to present the most relevant information first? Then it would be easy to capture people’s attention and keep them engaged for longer periods of time. But how do you determine what is relevant? Their answer was to use data from engagement with past content to predict whether new content is likely to be relevant or not. Therefore, social media companies developed proprietary algorithms that leveraged machine learning (an interdisciplinary field that uses tools from math, statistics and computer science to detect patterns in data) to automatically identify the types of content that each person will engage with. As we interact with these platforms, the algorithms learn what we like to see and continue to present us with more of that sort of content. If you are a sucker for puppies and you often click on, like or share content related to puppies, then you can expect that your feed will prioritize that sort of content. If there are certain particular political issues that grab your attention and cause you to spend more time looking and less time scrolling than other posts, then you can expect to see that sort of thing show up more often in the future.

These algorithms are not static, they change over time. They respond to our behavior which makes it possible for feedback loops to emerge. Our tastes and behaviors influence the algorithm, which influences the content we see. If that content influences our tastes and behaviors (which it almost certainly does), then the algorithms will adapt, and the cycle can continue indefinitely. The result is that we see more and more of the sorts of things that the algorithms think will grab our attention, and less and less of the things that do not.

Some have expressed concern that these algorithms could reflect the biases of their programmers. If the employees of Silicon Valley companies have biases, then that could bias the content that gets promoted on their platforms. However, I believe that there is a far more dangerous threat inherent in this process. Since most of the content that we see is selected not by humans but by computer algorithms that are designed to learn our preferences, the biases in the content we see are far more likely to be our own rather than those of the programmer. What this means is that our social media feeds will learn to present us primarily with content that we agree with.

This can result in phenomenon known as an echo chamber. Our social media worlds can evolve into a bubble in which we are surrounded by people who think and talk much like us. Within these bubbles, our views are rarely challenged, and they are often reinforced by the shared views of the people around us. In an echo chamber, the people we interact with are like-minded, so we can convince ourselves that our ideas are normal and acceptable, even when that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The fact that we are able to join groups and make connections with strangers who we never would have interacted with before serves to exacerbate this phenomenon. It allows us to self-organize around common values, interests, or beliefs instead of geographic proximity. When like-minded people interact, they tend to become more like-minded and the resulting homogeneity can promote a sense of community and of strength in numbers. That may sound like a good thing. After all, who doesn’t want to get quick access to the things that interest us and who doesn't like the feeling of belonging to a community? But what happens when that content is inaccurate or harmful? What happens when the unifying thread of a community is hatred of another group? What happens when the common belief is a conspiracy theory? The sad reality is that social media platforms make it easy for those types of content and communities to proliferate and flourish. This can cause hatred and ignorance to become more entrenched.

Before social media, these echo chambers were much harder to sustain. Our social networks were driven who lived nearby. As a result, it was difficult for our networks to reorganize and become homogeneous. However, on social media, we can friend and unfriend (or follow and unfollow) with the click of the button and there are no geographic constraints on who we interact with. As a result, the solidification of these bubbles has accelerated, and communities can spring up over night around ideas that could never have gained a foothold before. Within an echo chamber, there is a feeling of familiarity and people feel more comfortable voicing thoughts in public that previously would only have been discussed in private.

This is particularly problematic in the context of news and politics. A growing percentage of the population uses social media as one of the primary tools for accessing the news. Instead of reading newspapers or checking the web pages of reputable news sources, many of us now get our news through algorithmically curated social media feeds. The posts that show up in our feeds are not random, nor are they a representative sample of the daily headlines. The news that shows up in our feeds is selected for us by black box algorithms that few if any people fully understand. To make matters worse, some of this "news" is provided in the form of text shared without proper attribution making identification of the original source quite difficult and verification of the claims next to impossible.

If the news that we are presented with comes predominantly from one particular viewpoint, it can bias our understanding of current events. Similarly, if our understanding of political issues is shaped by a narrow subset of the political landscape, then it can shift our views on those issues. In an echo chamber, we tend to be exposed to news and commentary that reinforces our preconceived notions. If we don’t like a particular candidate, then we will tend to engage with content that is critical of that candidate and as a result the curation algorithms will learn to present us with more of that sort of content. This often serves to heighten our dislike for the candidate leading to a vicious cycle. In a normal, functioning society (which sadly seems to be an elusive concept these days), this process would be counteracted by interactions with people of differing perspectives. Before the rise of cable news and social media, this was commonplace. Schools, churches and other community groups served as a forum where people interacted with neighbors and friends regardless of their political leanings. However, when echo chambers form, those interactions become scarce and our views tend to become more fixed.

Now you may be thinking, what is wrong with holding tightly to your beliefs? I would argue that strong beliefs are not the problem. One problem is that strongly held beliefs need to be subjected to scrutiny from time to time, otherwise we may never realize when our beliefs are just plain wrong. If we are never challenged, then we may never be forced reflect on the reasons why we hold those beliefs and as a result, our misguided beliefs can easily persist.

Another problem is that strongly held beliefs are often be accompanied by antagonism for those who do not share those beliefs. When we interact with those who do not share our beliefs, it helps us realize that they too are people and that they too may have good intentions and even good reasons for their beliefs. Even if we are not persuaded by their arguments, and even if we think their methods are misguided, interacting with people who do not share our beliefs can help us learn to understand, respect and show compassion towards others. In an echo chamber, our passion for our own beliefs grows but our understanding of the alternatives does not.

I believe that this is precisely what we are seeing in our culture today. Republicans and Democrats are not just opponents, they are enemies. Conservatives and progressives do not just disagree, they hate each other. They don’t think the other side is wrong, they think they are evil. They don’t think the other side is misguided or misinformed, they think the other side is intentionally working to destroy the things we hold dear. With that level of polarization, productive civil discourse is not possible and cooperation is not an option. Bipartisan collaboration is out and negative partisanship becomes the norm.

We see evidence of this in the ways that we interact on social media. On twitter we see that people rarely follow or retweet people from across the aisle. The visualization below reflects the pattern of retweets about political hashtags during the 2010 election. Each node represents a twitter account (with colors to indicate political preference: blue for progressive and red for conservative) and each line represents a retweet. Notice that red accounts rarely retweet from blue accounts and vice versa. This phenomenon has become even more pronounced in recent years.

So how did we get here? How we become so divided? In this post, I have tried to present a narrative explaining how social media has contributed to this phenomenon. It is not the only factor, but it is a significant one. And in case you were wondering what the math says (this blog is supposed to be about “current events through a mathematical lens” after all), it suggests that social media is a remarkably effective mechanism for enhancing polarization and creating echo chambers.

There are many mathematical models that have confirmed this, but I would like to look at one that has a demo that does a nice job of illustrating this phenomenon in action (https://osome.iuni.iu.edu/demos/echo/). It has some neat visuals and is easy to use, so I would encourage you to play around with it if you have time. Note: I recommend turning the speed up to the maximum level.

In this model, the authors (from Indiana University) describe a social network consisting of people (colored circles) and reciprocal social media friendships (represented by gray lines). Individual nodes (people) are colored according to the political beliefs of each person with blue representing progressives and red representing conservatives. Initially, these beliefs and friendships are distributed randomly across the network, but this distribution is allowed to change over time as the following four types of events are simulated:

Users read messages posted by their friends.

Users change their opinions slightly when exposed to messages that they agree with.

User unfriend people who post things they disagree with and befriend someone new (at random).

Users post their own messages or repost messages from their friends.

These interactions were designed to mimic the interactions that take place on platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

The effects and frequency of those events are determined by three parameters:

Tolerance – This affects how flexible people are when determining whether a message is concordant, i.e. whether they “agree” with it. This affects their willingness to be influenced, to unfriend and to repost. The higher the tolerance, the more willing people are to consider a message to be concordant with their own views.

Influence – This affects how quickly people change their views in response to concordant messages. If Influence is strong, then people change their views quickly to match the views of their neighbors.

Unfriending – This determines how frequently people sever ties with friends who post discordant messages. If people unfriend often, then the network structure changes quickly.

They explore variety of different scenarios:

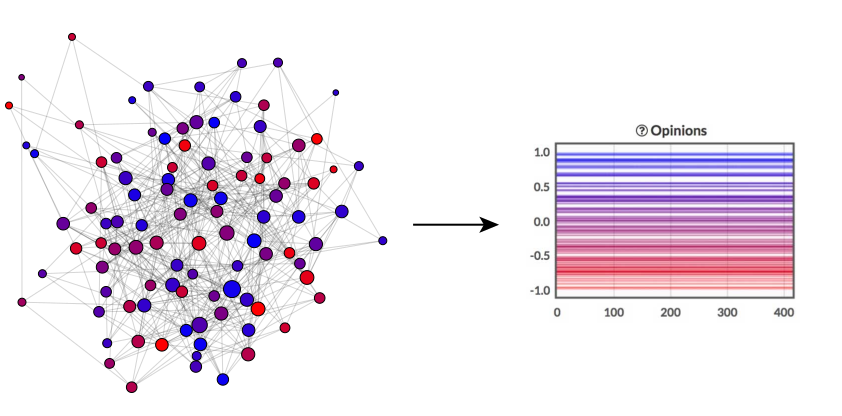

1. Static (Tolerance: Medium, Influence: Off, and Unfriending: Never): In this scenario people never change their views, so nothing happens. They may not like what their friends post, but the system remains unchanged.

2. Easily Influenced (Tolerance: Medium, Influence: Strong, and Unfriending: Never): In this scenario people never change friends, but they are easily influenced. So, the network tends to evolve toward a state where everyone is a moderate or where progressives and conservatives coexist and remain friends.

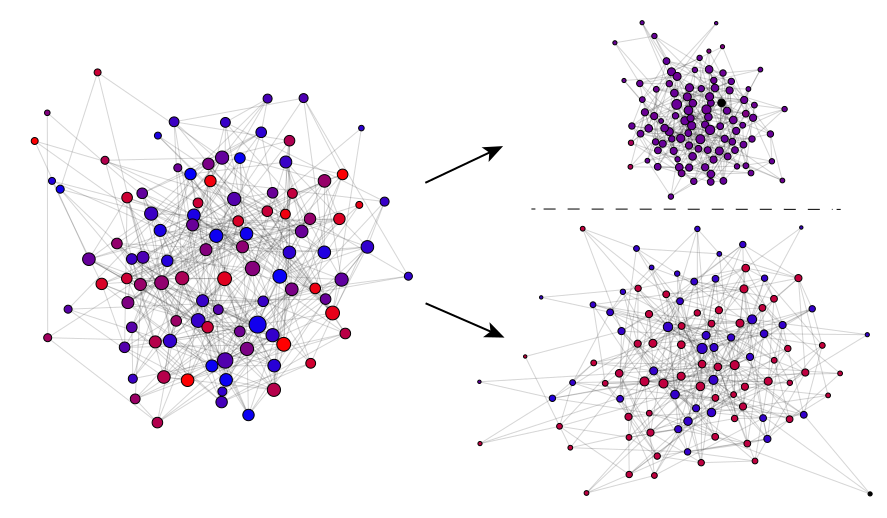

3. Fair weather friends (Tolerance: Medium, Influence: Off, and Unfriending: Often): In this scenario people are never influenced by each other, but they often unfriend those they disagree with. The result is that the network breaks up into distinct clusters of conservatives, moderates and progressives and these groups rarely interact.

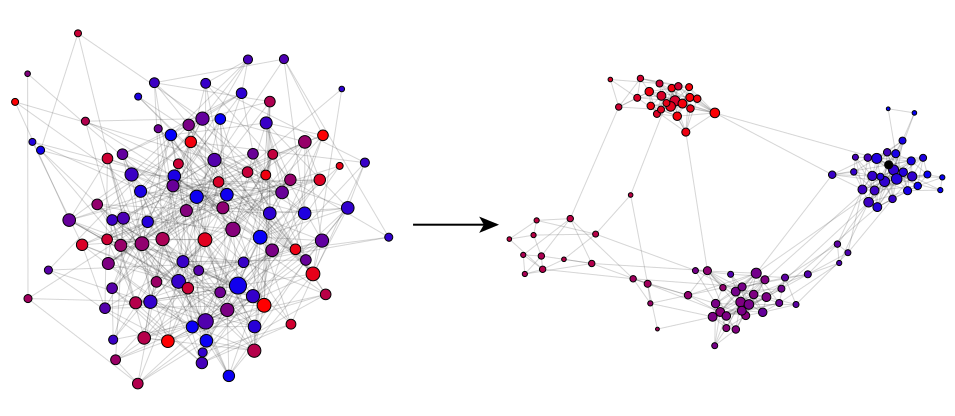

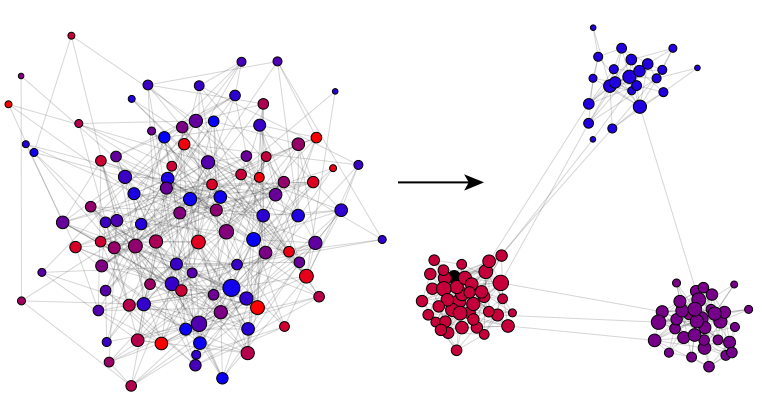

These first three scenarios are not meant to be realistic. They are just baselines to get a sense of how the model works. The interesting and more realistic scenarios are the ones that include both influence and unfriending. Here is one possible outcome with Tolerance: Medium, Influence: Strong, and Unfriending: Often

Notice that the system evolves toward a polarized state where the network forms very distinct groups of like-minded people with few interactions between these groups. This type of outcome is the norm. It doesn’t matter how strong the influence is or how frequent the unfriending is, as long as both factors are present, the system seems to become polarized and fragmented. The only exception is the case where tolerance is high, but I think we can all agree that a willingness to put up with messages that you strongly disagree with is a rare trait indeed. And here is the scary part, these are the realistic scenarios and they all end up in this polarized state where everyone lives in their own echo chamber.

This is just a toy model, but it illustrates the essential factors in play and it suggests that, in a world where it is easy to influence each other through shared messages and to rewire our social networks, echo chambers and polarization are inevitable. This is a troubling outcome indeed.

In a future post, I will look at some of the insights we can gain from these sorts of models and about how they can help us know how to combat misinformation and polarization.

PS. To learn more about the model, check out their preprint via the link above.

Comments